The Stages of Change Model developed by Dr. Ruth Freeman can help oral health professionals in their psychosocial approach with patients with disabilities. It provides a framework through which they can assess the progress of their patients from unawareness through motivation to compliance.

Disability poses a challenge for professionals in the field, but following these stages systematically can lead to success.

Stage 1: Precontemplation

Precontemplation is characterized by raising patient awareness regarding the need to change their behavior towards the dentist. The main technique used at this stage is motivational interviewing to assess readiness for change. At this point, the dentist learns about the patient’s concerns, emotional burdens, and desire for change; gathers information on comorbid diagnoses and medications; and engages with family members to better understand the patient’s daily barriers and how the dentist can adapt to them.

Stage 2: Contemplation

In this stage, the patient with disabilities—especially those with moderate levels of communication and interaction—is more involved in conversations with the dentist. This happens once the dentist introduces the patient to the instruments that will be used during a dental procedure.

The mirror becomes the main tool through which the child observes their oral condition: cavities in frontal and distal teeth, or a loose tooth being moved in front of the mirror to understand why it must be extracted. Through simple explanations, the child begins to realize how bacteria in the mouth overpower the body’s defenses, engaging in a process of deeper reflection and awareness—a conscious “battle” against bacteria.

Stage 3: Preparation

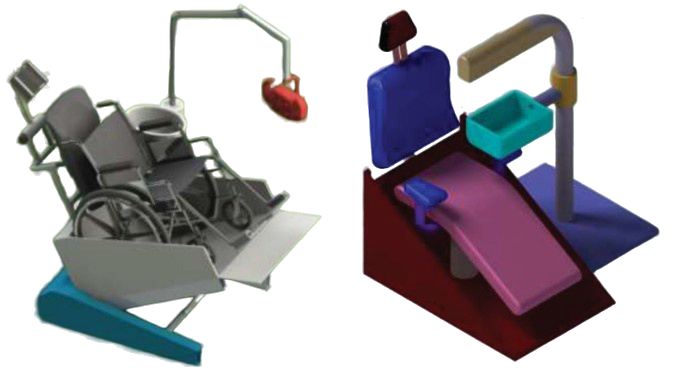

The preparation phase enhances awareness, self-image, and readiness for change while supporting behavior management. The patient is introduced to the clinic environment: photographs displayed on the walls showing bright smiles, or before-and-after illustrations of children in pain who later appear relieved and happy.

A multidisciplinary team—dentist, assistant, anesthesiologist, developmental therapist—may use interactive exercises, such as applying toothpaste to the child’s lips in front of a mirror, to help them familiarize themselves with dental procedures like fillings, the smell of airflow powder used after plaque removal, or orthodontic brackets for teeth alignment.

Stage 4: Action

When patients reach the action stage, they have resolved their internal conflict. They need strong support during this critical period, as their newly acquired behavior is still vulnerable to both positive and negative influences. Dentists must strictly follow protocols tailored to patients/children with disabilities.

The dentist should speak directly to the patient in the first person, using a slightly stronger tone to guide non-standard behavior in the dental chair. Patience, empathy, and clear step-by-step explanations of each instrument and procedure are crucial in this stage.

Stage 5: Maintenance

After treatment, it is essential for patients to attend regular check-ups with their dentist, reflecting shared responsibility in preserving oral health improvements. Patients/children with disabilities who reach the action stage benefit from shorter, more focused interventions and actively participate in subsequent sessions. They take responsibility for their oral health while acknowledging the supportive role of the dental professional.

Stage 6: Relapse

Relapse in patients with disabilities occurs when maintenance strategies break down and previous unhealthy behaviors re-emerge. Though common and often seen as a setback, relapse provides an opportunity to re-negotiate health goals.

An Italian implantologist shared a useful technique for home oral care to prevent deterioration and relapse: using a toothbrush with extra-soft bristles, soaking it in optimally warm water to further soften the bristles, rinsing with cold water, and applying a fruit-flavored toothpaste of the child’s choice. Brushing should be quick and gentle with short strokes across both jaws. Over-brushing or prolonged brushing may create discomfort, making the child more resistant during future sessions.

Insights from Dr. Ruth Freeman

Dr. Ruth Freeman, a distinguished lecturer in public dental health at the School of Clinical Dentistry in London, highlights that dental professionals must strive to understand the psychosocial background of their patients as well as their reactions to the care they receive. She emphasizes that 65% of all communication is nonverbal with patients with disabilities. Nonverbal cues are often trusted more than spoken words. As the saying goes: “Actions speak louder than words.”